Vaslav Nijinsky - paintings / drawings - Raw Vision Magazine, 2016

"For a short period of time, from 1918-19, not long before mental illness completely overtook his life, Vaslav Nijinsky created a group of drawings and paintings. In contrast to the volumes written about Nijinsky the dancer/choreographer, there has been very little consideration given to these works.

The Nijinsky paintings and drawing are intimate in scale, the paper he surfaced was 30 x 37 cm or smaller. Although the proportions are modest, the images are powerful. It can be a challenge to remember that these works are almost one hundred years old, since they appear both current and timeless.

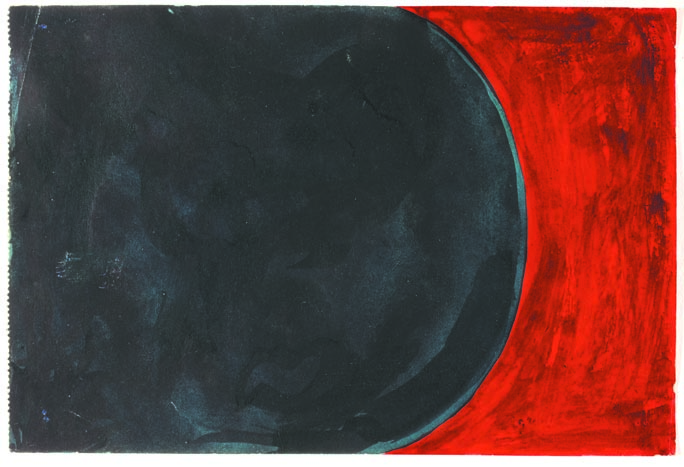

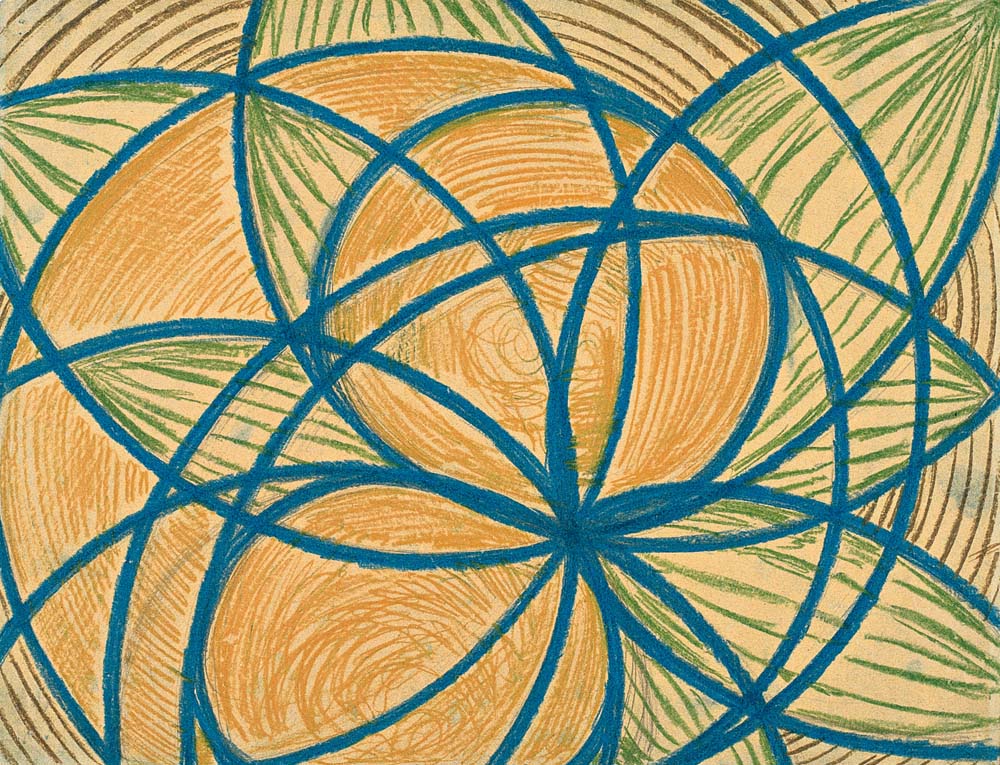

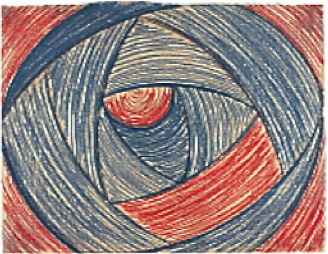

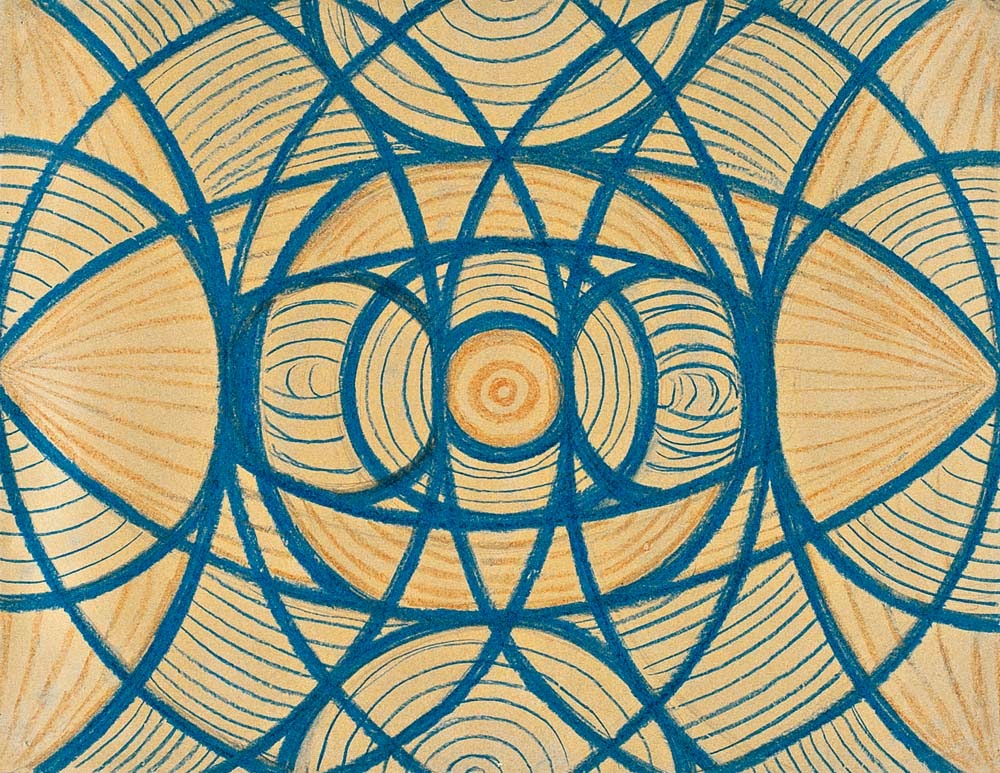

Nijinsky used ink, crayon, pencil and paper as mediums. The crayon and pencil drawings have a geometry defined by circles. These works are obsessive and hyper-focused. When he used ink on the page, emotions define the picture plane, as well as revealing a sense of spontaneity.

Viewing only one or two of these pieces, particularly the drawings, gives the impression that Nijinsky may have simply been exploring a decorative geometry. But when exposed to a larger group, the obsessive nature of Nijinsky’s drive is evident. Variations and themes, applied with line, energize each page. A sense of urgency emerges, as if the artist felt compelled to explore every possible configuration of one simple concept.

Since few facts are known about his motivations, it is a complex task to establish Nijinsky’s place in the history of twentieth century art. Likewise, insufficient reliable information exists as to the meaning of his iconography. Attempts have been made to define this art, but in general these interpretations have been based on conjecture.

It is particularly unwise to make assumptions about Nijinsky. His life was exceptionally unconventional. Most contemporaries who wrote about him had a self-serving agenda and were hardly concerned with truth and accuracy. When Nijinsky is quoted in his own words, it is usually from a group of notebooks he kept at the same time he was making this body of work. While fragments of these journals seem logical and coherent when taken out of context, the majority of the writing exposes a man struggling with the onset of profound mental illness.

What is known about Nijinsky at the time he created this art is that he was a highly informed individual. It would be naïve to interpret these works as simply the efforts of a mad man. Just a few years before he began making paintings and drawings, Nijinsky lived at the epicenter of European avant-garde culture. Many historians consider his collaboration with Stravinsky and Diaghilev to be the event that set in motion a century of revolutionary creative energy in every field of Western art.

Most likely, Nijinsky was in an overexcited state in 1918 when he rented a home for himself and his family in St. Moritz. His writings at the time reveal the type of intensity often associated with mania. However, interpreting Nijinsky’s art solely through the prism of mania or another mental illness is too limiting. Elevated emotions may have driven Nijinsky to create a large body of work in a relatively short time, but his raw and visceral imagery reflects the intent of a man still in control of his vision.

Like many early twentieth century artists who transitioned their art into pure abstraction, several of Nijinsky’s works have a trace of representational form. On more than one occasion, Nijinsky stated he was rendering the eyes of soldiers, attempting to express on paper the devastation he saw in the faces of those who had experienced the horrors of the First World War. In other compositions, circles are arranged in such a way as to suggest a face. Nijinsky’s wife Romola titled these works, “Masks”.

While a literal meaning may be implied in Nijinsky’s art, what is apparent in almost all of his works on paper is a heightened emotional energy expressed through abstraction. As this work was created between 1918 and 1919, many are unprecedented examples of pure abstract art. It is not known if Nijinsky was influenced by or even aware of Malevich’s 1915 painting, Black Suprematic Square. But like Malevich, Nijinsky was exploring uncharted territory, pursuing a direction that was decades ahead of even the most progressive painters of his time.

What separates Nijinsky’s works on paper from other early abstract art is the vigorous sense of emotion he conveys. Early non-representative art was cerebral, fueled by intellectual discourse, often defined in manifestos. But Nijinsky’s art, particularly when he applied ink to paper, is more in keeping with the Abstract Expressionists, a movement he predated by over twenty years.

Nijinksy composed a total of one hundred and fifty-six paintings and drawings when he was living in St. Moritz. Currently, one hundred and thirty-four have been located. The Foundation John Neumeier in Hamburg, Germany owns ninety-two pieces. Nijinsky’s wife also donated several works to the Musée de l'Opéra de Paris.

A dancer and choreographer, John Neumeier is the director of the Hamburg Ballet. Since he was a young man, he has been fascinated with Nijinsky. His collection, which became the Foundation John Neumeier, holds a wide range of objects associated with him. The Foundation acquired the paintings and drawings in the mid 2000’s. Previously, this work was owned by Nijinsky’s heirs and rarely seen by the public.

Nijinsky’s artwork is still waiting to be discovered. Over the past few years, selected drawings and paintings have been exhibited internationally. The most important institution to show his art has been the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. In 2012, three pieces were curated into Inventing Abstraction, 1910 – 1925. Unfortunately this group show did little to expand the awareness of Nijinsky’s paintings and drawings.

Art historians, scholars, and museum curators have overlooked the art of Vaslav Nijinsky. Although his time as a painter was short, he left a body of work that is important. He was one of only a handful of men and women committed to pure abstraction in the earliest years of the twentieth century. Few of his peers were as bold. It is time to embrace and acknowledge his innovations as a visual artist."