Tasking Beauty - Sculpture Magazine, June 2012

"Steven Emmanuel’s sculptures are restrained, understated, and cerebral. Works are built on a foundation of simple conceptual ideas, culminating in forms that are exquisite. As if fabricated by a craftsman, these intellectually conceived pieces are as beautiful as they are thought provoking.

Intrigued with process, Emmanuel builds objects that reveal their fabrication. His sculptures grow from a series of simple repetitive tasks, such as sorting, nailing, or the folding of ordinary materials. These common acts give physical form to Emmanuel’s vision. The sculptures require patience more than skill to construct, yet always transcend the mundane.

Emmanuel, who is 28 years old, received his MA from the Royal College of Art in London. His sophisticated work reflects a formal art education. Yet, the obsessive orientation apparent in his art is reminiscent of the efforts of many self-taught/Outsider artists. With a hyper-focus on details and process, Emmanuel’s pieces are infused with a personal iconography that seems to ground him and to define purpose.

The sculpture, Sorting the Hundreds from the Thousands, is an object that embodies all aspects of the artist’s philosophical perspective. Two small, clear plastic cups, filled with the sugar candy used to decorate cakes, sit side by side. In one cup, the candy has been layered into color stripes; in the other, elements are thoroughly random. This sculpture kept Emmanuel at a desk for six months…sorting and ruminating.

On first impression, the work seems obvious and straightforward, but in fact it is just the opposite. Sorting the Hundreds from the Thousands is a complex effort, full of contradictions. Reflecting on the sculpture, Emmanuel writes, “This piece of work was quite epic for me. I was thinking a lot about order; choice; intervention; aesthetics; labor; socialism; class and everything under the sun as I had six months to dwell on my thoughts.”

Addressing the ephemeral nature of the work, he adds, “The hundreds and thousands are as important in their existence outside the gallery as they are inside. Now that they have been put in to the cups they are never to come out or be resorted. The work is so fragile it can only be delivered by hand with the utmost care. Over time and a period of exhibitions I expect they will subside and reform into their original state. It is my job to protect them from this fate or at least prolong this from happening. It’s kind of like a game. I have to hand deliver them wherever they go as they cannot be shipped. It is almost like a performance piece itself, when I am traveling around holding these two cups for dear life across busy train platforms and getting into cabs, people look at you in the strangest of ways.”

That such a piece so small, so fragile, can be perceived as “epic” exposes Emmanuel’s artistic sensibilities. He speaks with a humble voice, without pretense. It is as if, through his work, he is whispering in our ear, inviting us to join him for a moment, to experience subtle ideas and their possibilities.

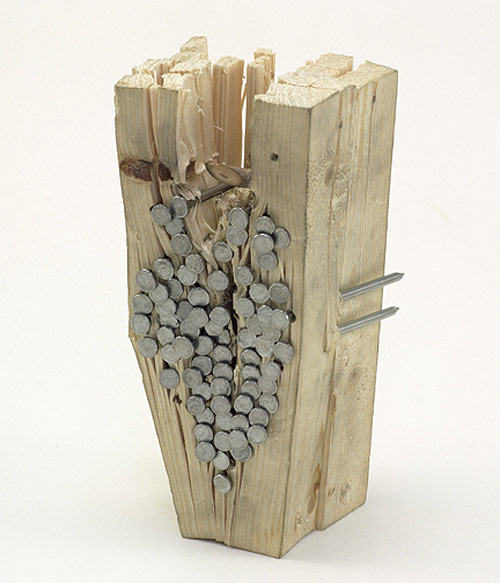

While Sorting the Hundreds from the Thousands is delicate and nuanced, almost jewel like, the sculpture Matrimony could not be more different. Matrimony is a work of raw beauty made from a bag of nails and two blocks of wood. To create Sorting the Hundreds from the Thousands, Emmanuel needed to work with a surgeon’s hand. To build Matrimony, he proceeded like an unskilled laborer, relying on brute force. Yet even as material, form, and fabrication differ in each of these works, there is a conceptual underpinning that is consistent in all of Emmanuel’s art. Simple acts, in this case nailing, become ideas revealed in completed forms.

Talking about Matrimony, Emmanuel explains, “The piece of work is about relationships and I think that is why I chose to call it Matrimony. The marrying of two things together, the basic idea is literally to create an object based upon the codependency of its materials. The relationship between the nails and the wood locks them both together. The nails hold the wood together and in turn the wood holds the nails together. Now they have been used in this way they can never come apart or they will fall apart. They exist in unison.”

At times Emmanuel’s work is almost playful. Paper Weight, commissioned by the National Glass Centre at the University of Sunderland in 2010, is simple and direct. Emmanuel carefully stacked ten thousand sheets of paper and topped the pile with a common glass paperweight. Seen in the context of the National Glass Centre, Paper Weight appears to be the effort of a trickster. What is the viewer seeing? A glass ball on a pedestal of paper? A conceptual installation? A sculpture in response to a word play? In this setting, Paper Weight is ambiguous, inviting interpretation and translation.

Unlike most conceptual artists, who focus more on ideas than on aesthetics, Emmanuel has an innate sense of beauty. His response to materials is rarefied; Paper Weight is a beautiful work. He intuitively sees the value in the most humble materials and pushes that potential. Be it the color and fineness of the paper, or the luminosity of the glass ball in contrast to the variegated edge of the column, each element is finely tuned.

While Paper Weight was conceived for a gallery setting, another work, Inside the White Cube, has yet to define its purpose. More than any of Emmanuel’s sculptures, White Cube takes the notion of art propelled by task to the extreme. Creating from almost nothing, he applies thin layers of paint to a paint dab in the palm of his hand. Every day he adds new layers and slowly the form grows. To date, he as gone through a 5 liter tub of paint and is now on a second.

This undertaking is an intensely personal endeavor. Emmanuel states, “My solid ball of white paint is slowly but surely getting bigger and bigger. I will continue this process for the rest of my life. I hope that at some point in my lifetime it gets too large to house and will exist outside of the gallery and make a strange and laborious transition to becoming a public art piece.”

White Cube is reminiscent of the works of eccentrics who aspired to wind the biggest ball of twine. Yet Emmanuel is not at all an eccentric and he has not conceived this sculpture as an oddity. Here the object is a framework that gives physical presence to the artist’s self imposed commitment to an endless task. There is no clear purpose to White Cube, it exists only as an obligation that challenges the notions of conventional art making.

Emmanuel’s art gives form to ideas. Even without a signature style, the sculptures are closely connected conceptually. Enhanced by the careful manipulation of materials, his works solicit observation and contemplation."