Saner - my personal gods / my personal kings - Panta, October 2014

It is hard to think about Saner and not be reminded of the great Mexican innovators - Posada, Rivera, Siqueiros, Orozco, Kahlo, Bravo, Tamayo.

Throughout the twentieth century, Mexican artists were extraordinarily passionate about their country. While these men and women were sophisticated and fully aware of trends in Paris, Berlin and New York, it was always their home country that infused their art. Few places are as culturally rich, engaging and diverse as Mexico. Even in this time of hyper- globalization, Saner remains, like those Mexican artists before him, profoundly grounded by heritage.

While street art is seen as something new and edgy around the world, it is a tradition in Mexico that started in the first quarter of the 20th century. These early mural painters were as provocative as contemporary street artists are today. They pushed boundaries, confronted authority and considering themselves revolutionaries.

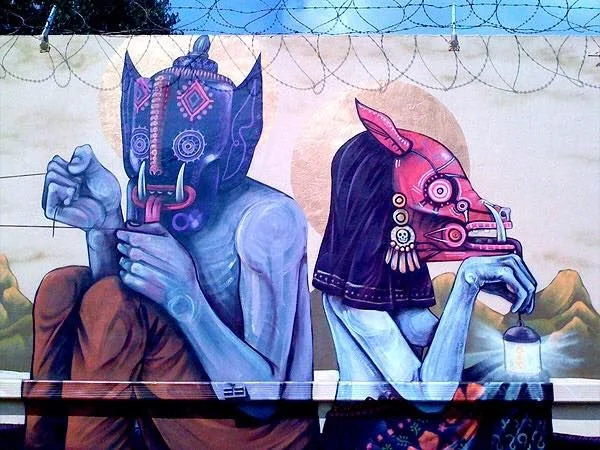

Saner lives in Mexico City, a place of raw energy and endless contradictions. When he talks about his home, he says, “Mexico is a surreal country. It has everything and nothing at the same time”. His art reflects this perspective. In almost all of his works, masks cover the faces of his figures. This suggests a world where everything is not as it seems. Saner explains this as metaphor, saying that we all put on a different face in different situations. Who is behind the mask, what role are they playing and why?

Masks have always been important in Mexico. It is possible to find examples in Pre-Columbian art and even today masks are an essential part of festivals that take place in all corners of the country. However Saner’s repeated use of this form suggests his connection to the mask is more personal than symbolic. Explaining this, Saner says “I take the mask from the Mayan culture. But, I want to create my own interpretation, my personal gods, and my personal kings. It's like a tribute in general of my roots.”

Saner has been drawing since he was a child and studied graphic design at university. The first mural he saw was a reproduction printed on Mexican currency. That modest observation changed his life and helped define him as an artist. The image was a detail of Jose Clemente Orozco’s 1926 mural, La Trinchera, which was painted in Mexico City. Even in this small format, Saner was moved by the power and potential of art.

The wall paintings Saner has completed are accessible and a bit playful. He has a seductive sense of color and creates intriguing imagery. In some of his murals there is a hint of violence, but Saner’s wall paintings are not menacing.

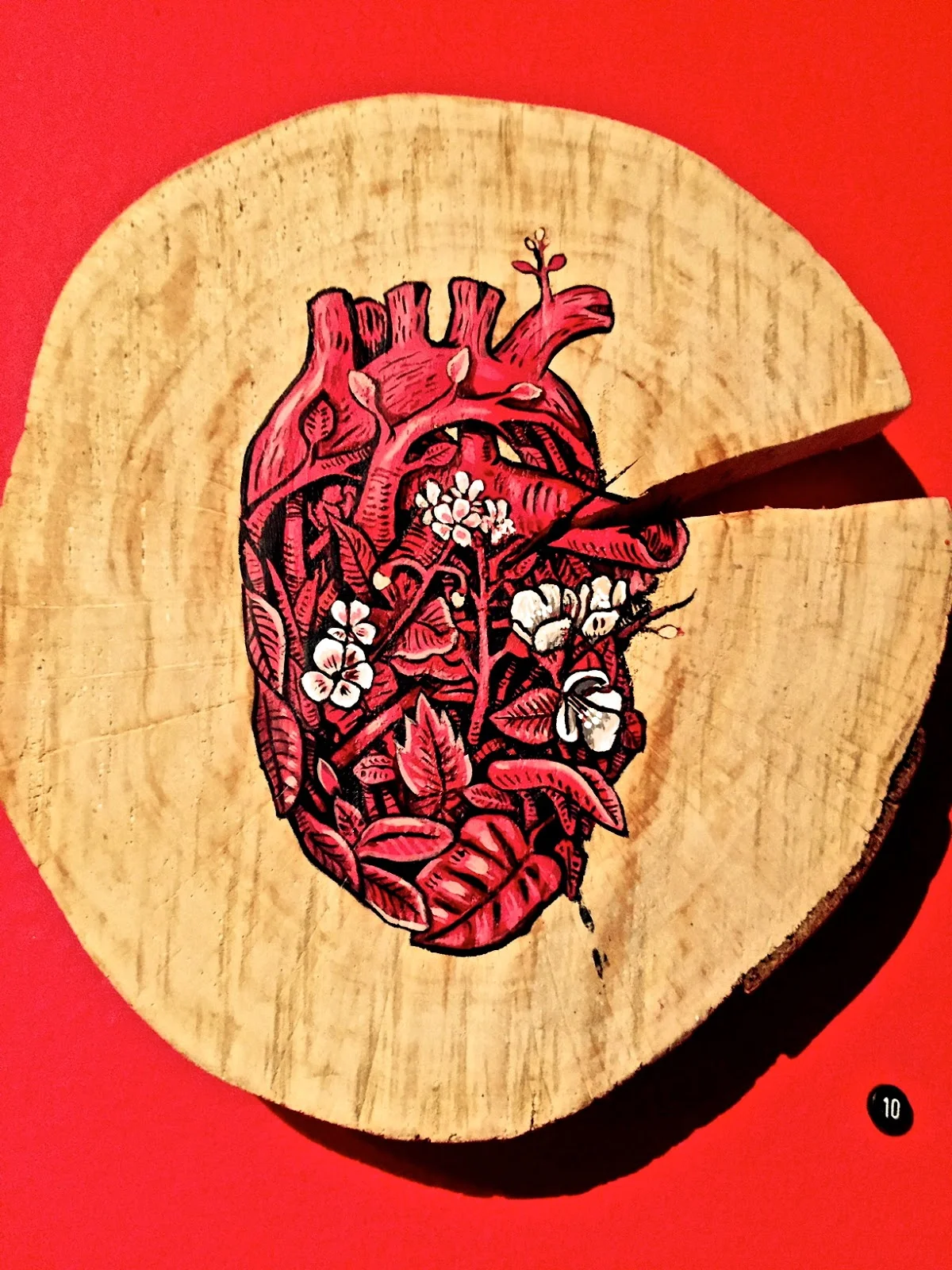

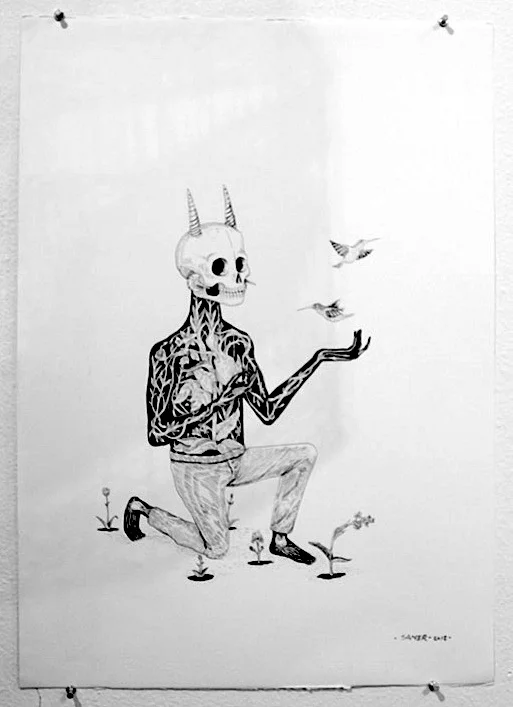

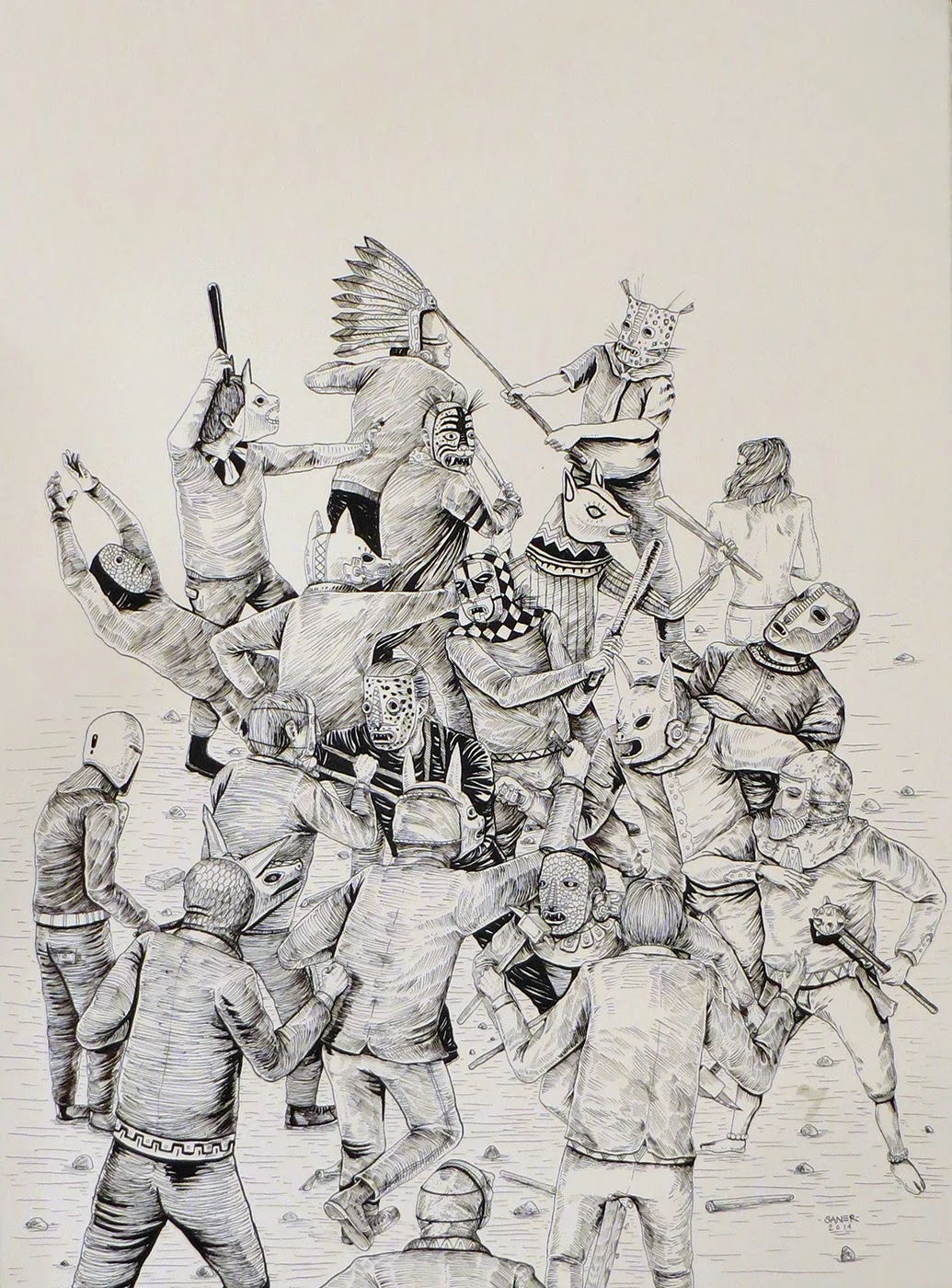

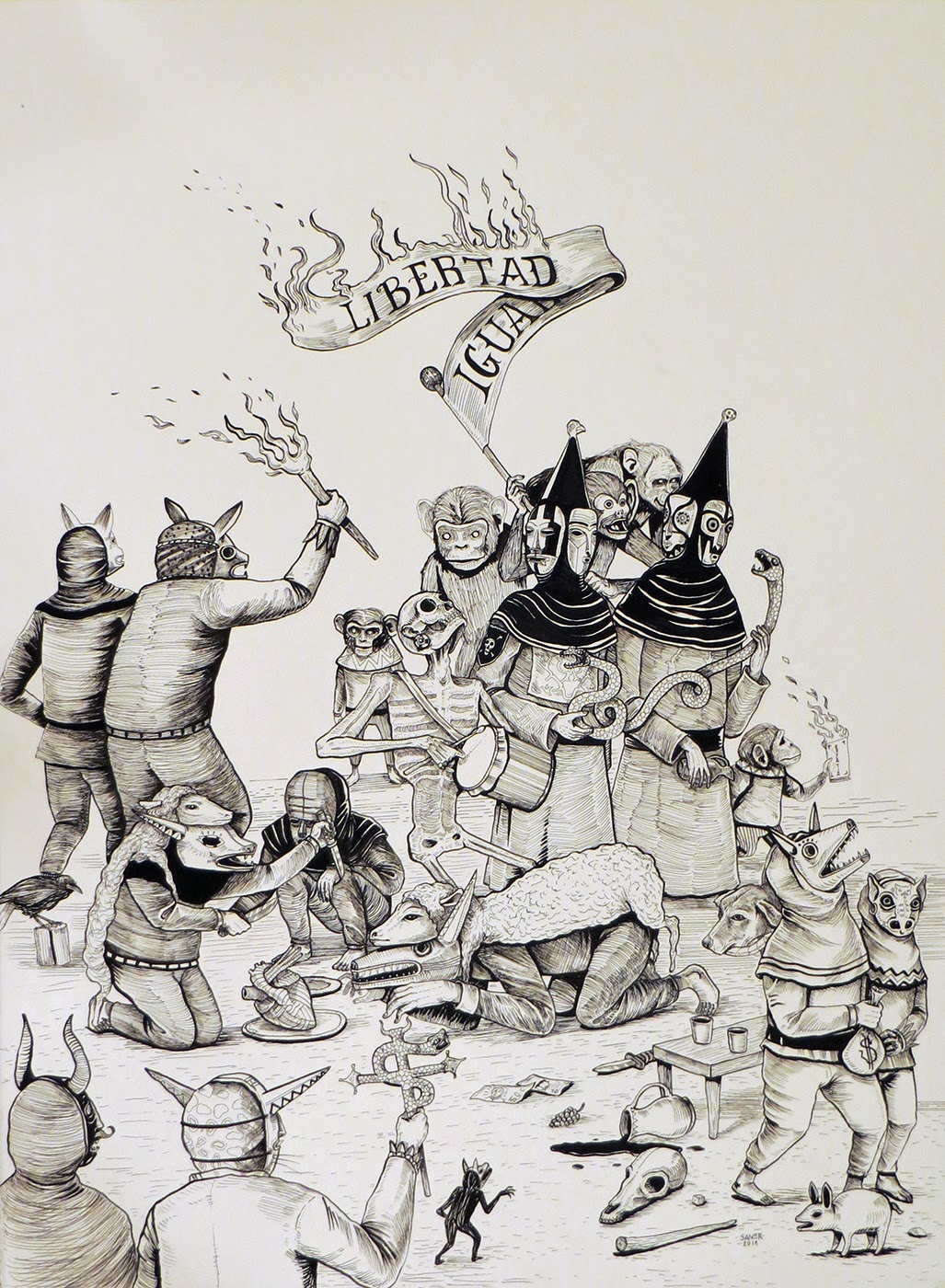

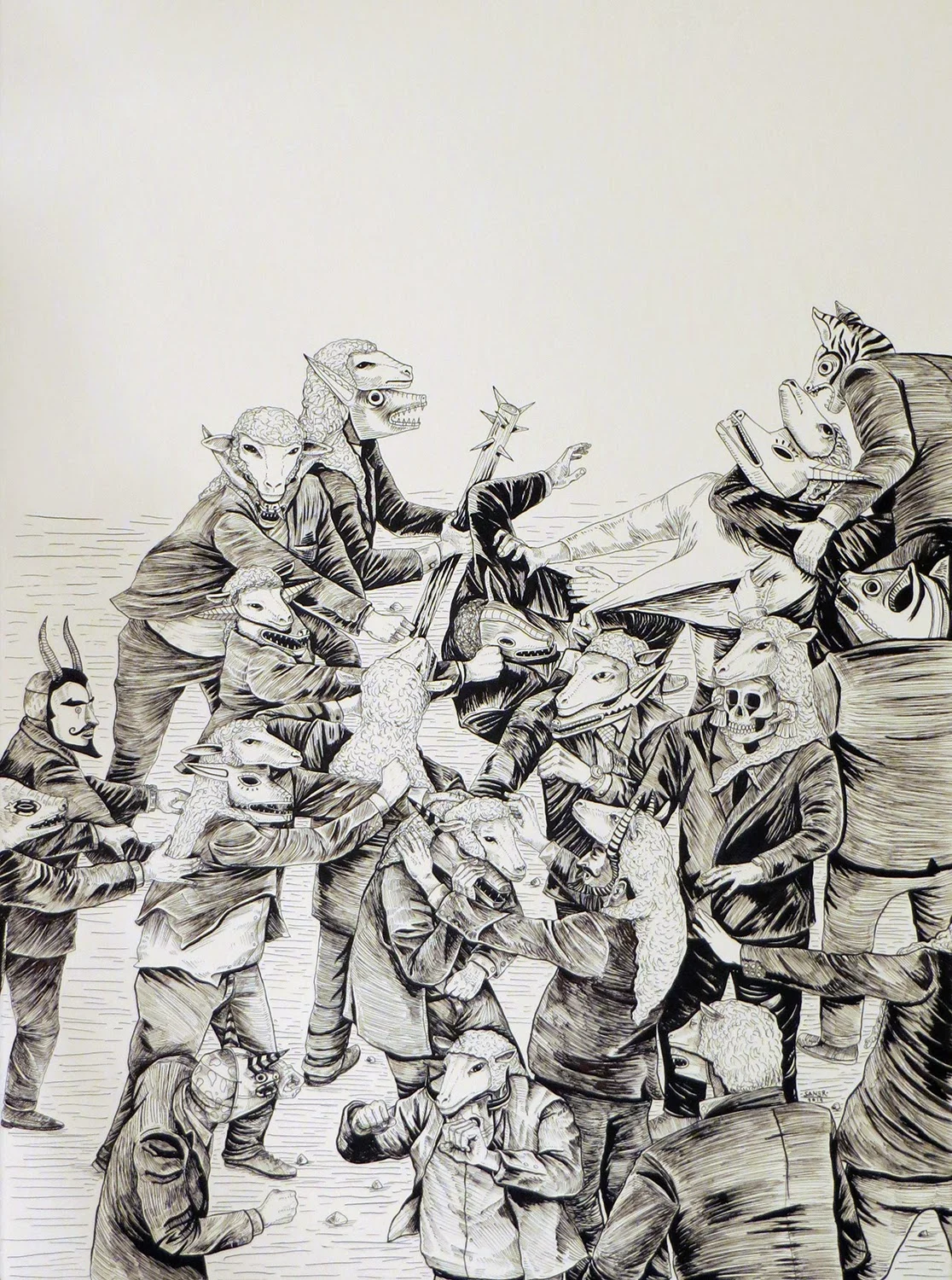

Like the great Mexican mural painters, Saner is an exceptional draftsman. It is in the drawings he renders that one sees his art at its most intense. These works often suggest brutality, existing beneath the surface or in plan view. The drawings have a heightened scene of focus and expose the artist’s determined concentration.

Saner’s drawings also reveals his visceral connection to Mexican iconography. The world around him and forms from the past appear reconfigured and reinvented when he takes ink or pencil to paper. In contrast to the monumental murals, Saner’s drawings are intimate, defined by their details. These works demand attention and present a narrative informed by observation and cultural continuity.

In recently years Saner has traveled the world to paint walls. Beyond Mexico, he has worked in Canada, Colombia, France, Germany, Italy, New Zealand, Peru, Spain, Tunisia, and the United States. He is part of a small army of artists who are transforming the international urban landscape and challenging assumptions regarding art in public settings. Yet Saner offers a point of view that is different from most of his contemporaries. In his work on walls, canvas, or paper, Saner shows that an artist can be both experimental and current, while at the same time deeply rooted in the past and legacy.

![FullSizeRender[2] copy 2.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5838fddc46c3c4b3910f61c6/1514236559962-PEVC5P3T28FTZLPHX2L2/FullSizeRender%5B2%5D+copy+2.jpg)