Pushpa Kumari – Upending Tradition - International Journal of Intangible Cultural Heritage, Summer 2020

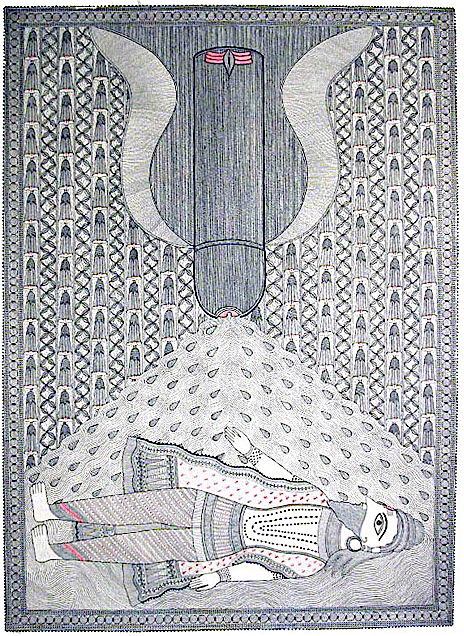

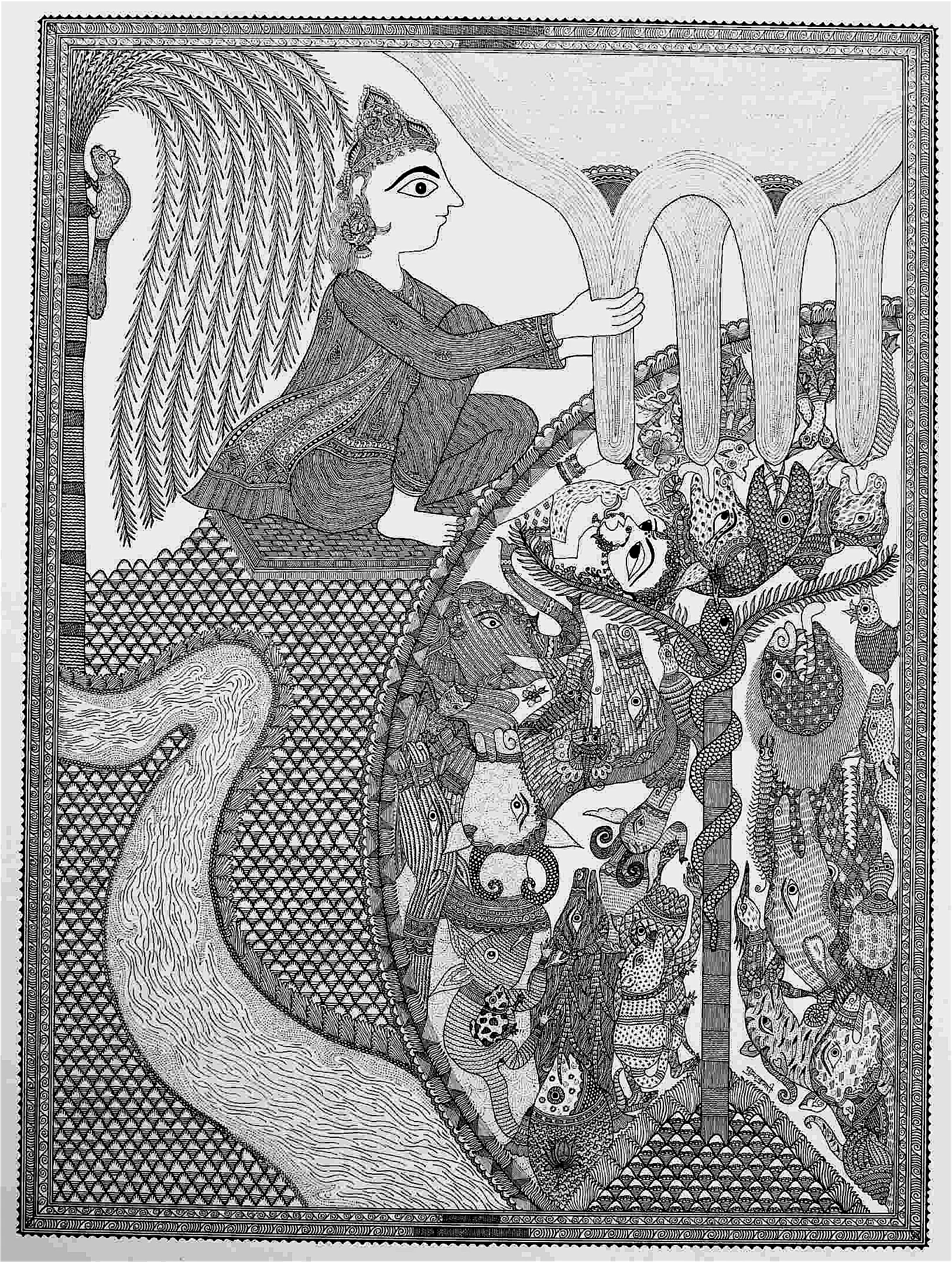

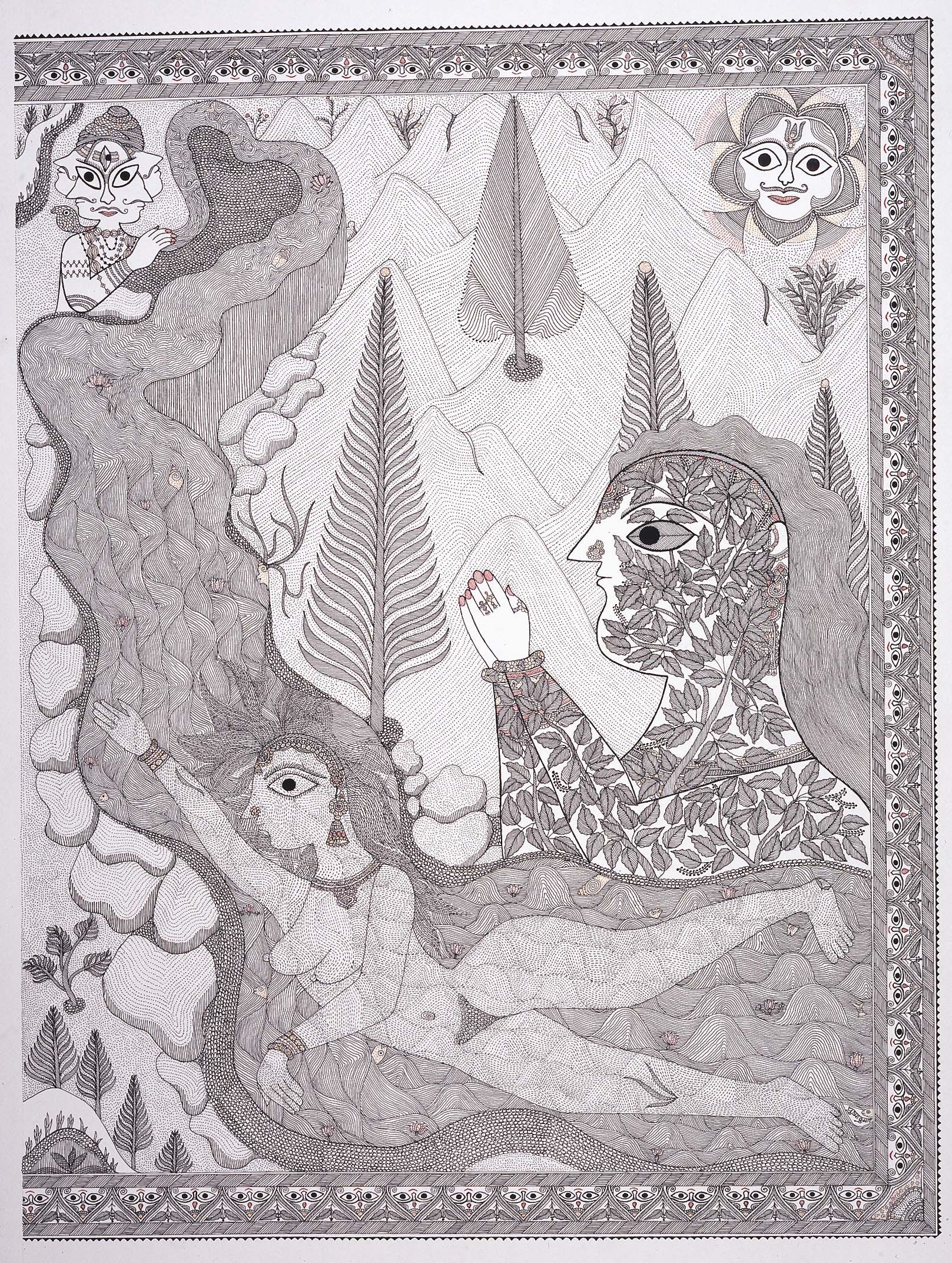

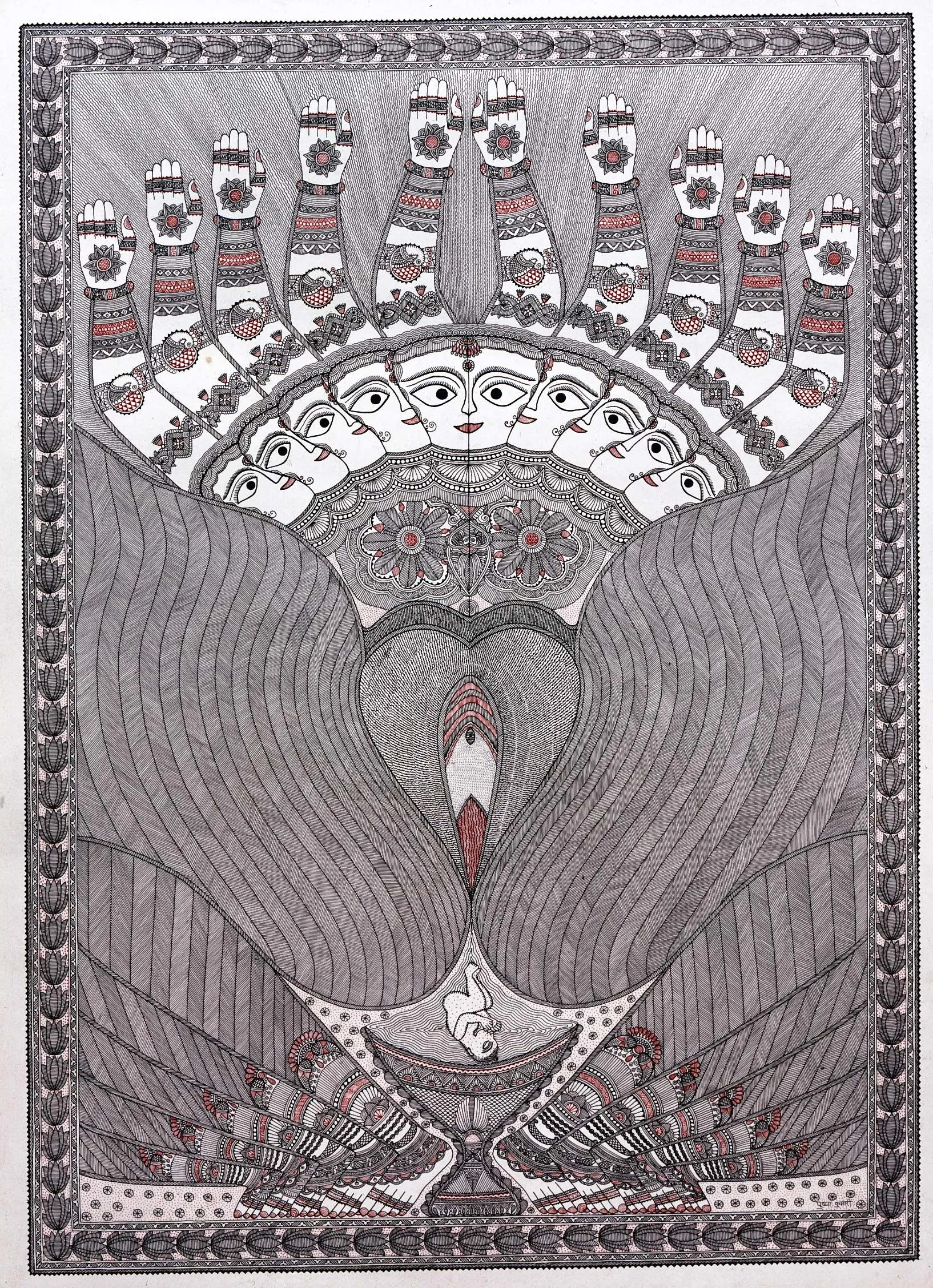

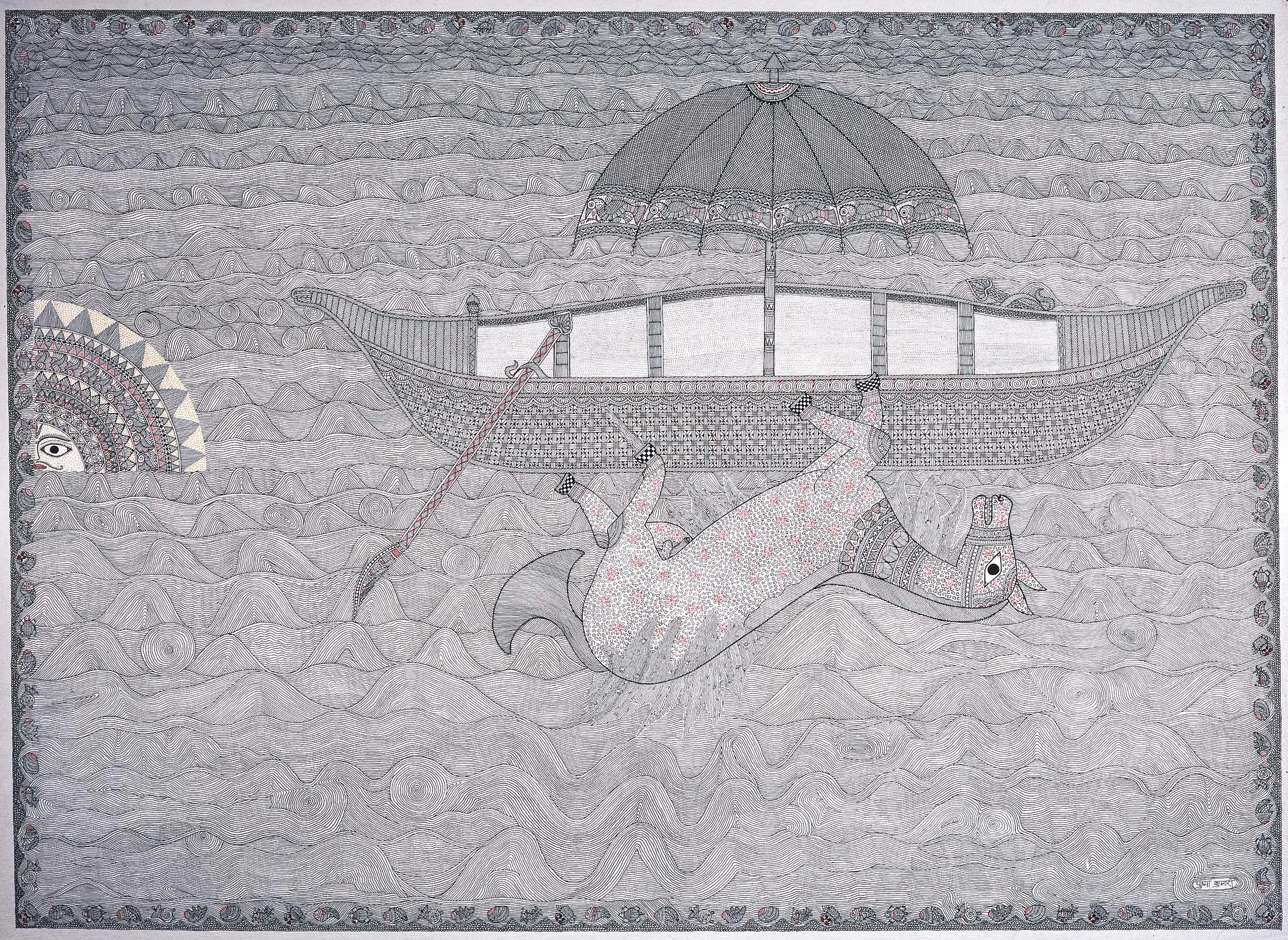

Lines on a page, deliberately rendered, brings to light a world imagined by Pushpa Kumari. Using only a pen and ink on paper, Kumari visualizes a domain energized by religion, heritage, astute observations and a highly intuitive personal sensitivity.

A woman in her early fifties, Kumari has devoted her life entirely to drawing. In a country of arranged marriages, Kumari remains single. She values her freedom and independence, focusing all energies on her art. By accepting an unconventional Indian lifestyle, she has been able to develop a unique body of work, different both in concept and form from her peers.

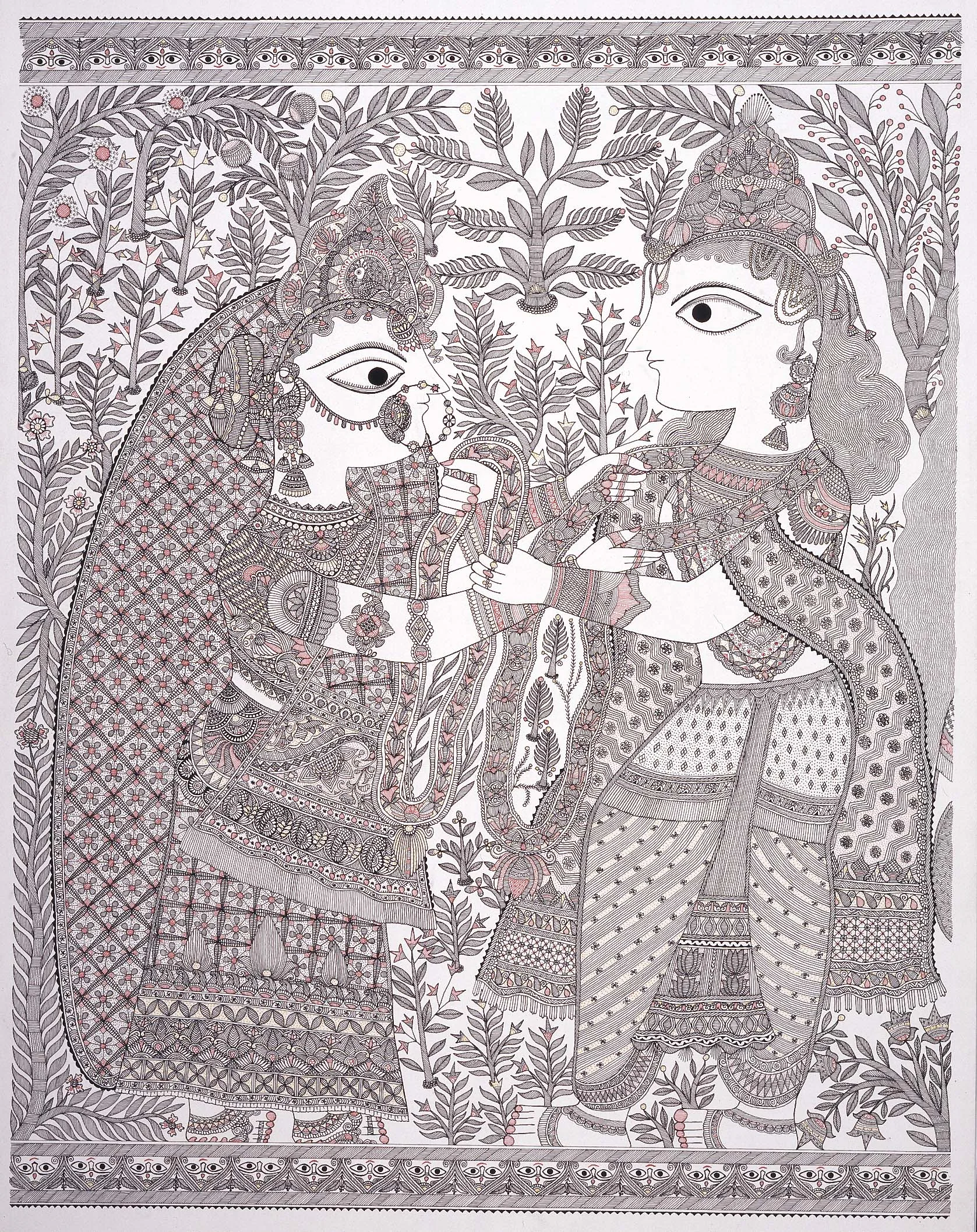

Born in a part of India known for painting, Kumari was surrounded by art. The women of Madhubani, Mithila, in the State of Bihar, have for generations embellished the floors and walls of their homes with complex, cultivated images. These works were not just decorative, but used to teach the epic Hindu myths to the children of the Mithila.

Kumari absorbed the artistic energy of the women closest to her, partially her grandmother, Maha Sundari Devi. Devi was one of the first women to explore the possibilities of applying the wall painting imagery on paper in the early 1960s. She was passionate and innovative, and an inspiration to Kumari.

While Devi made the transition from wall to paper, her renderings conform to the standards of Mithila culture. Kumari’s work transcends tradition, in approach, concept and intensity. Kumari has taken the basic elements of Mithila painting and created a lexicon all her own. She is informed by her heritage, but like most artists in the West, she creates drawings for reasons that are motivated by the personal, not driven by cultural obligations.

Kumari does draw subjects that at first glance appear traditional. However, she uses these images as a platform to build upon. When Hindu myths are depicted, the drawings are much more than illustrated stories. Figures interact, emotion is evident; Kumari presents her ideas with an intensity that communicates how completely absorbed she is in the creative process.

Kumari generally works within a modest format, drawing on sheets of paper approximately fifty by seventy-six cm. She has also created larger works by combining several sheets of paper. Like Japanese wood block triptychs, each page can stand alone as work in its own right, but when viewed together the images link in ways obvious as well as implied.

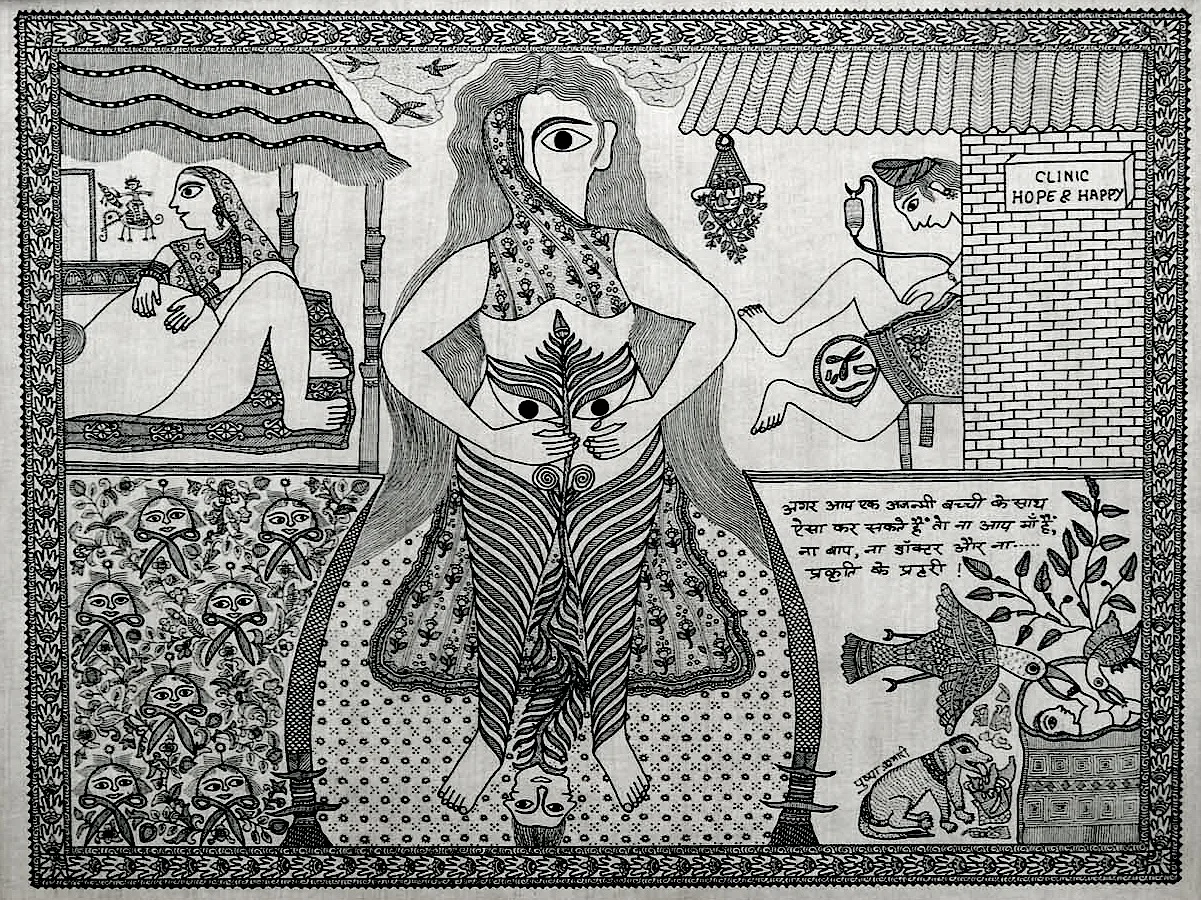

Kumari can be provocative in a simple small format. One untitled drawing, less than 23 x 30 cm, is emotionally charged and powerful beyond its humble scale. A scene that is repeated daily in rural India, behind closed doors, is revealed . . . female infanticide. The power of this drawing is overwhelming, almost unimaginable. Standing pregnant, back to a wall, a woman faces trauma from another, who lying on the floor for support literally kicks the baby from the womb. This brutal image is simply presented, with just the slightest of emotions suggested, three tears from the mother’s eye.

Here we see Kumari as feminist, aligned with the young women of India who may lose all their freedoms when married. Political in orientation, this work confronts the inequities and harshness of Indian society, straight on, without hesitation. Kumari has an especially close relationship with her many younger sisters, her mother, and grandmother, so it is not unexpected that women are often the dominant subjects in her drawings.

Western curators and critics often misunderstand artists like Kumari. It is common to see American and European curators visiting India to develop a show on the new “Indian” art. These professionals tend to gravitate to work that seems familiar to them. What they see as “contemporary” is often closely related to formats known in the West. However, Western art media and markets profoundly influence many Indian artists, resulting in efforts that are derivative, with a seasoning of heritage/nationalism.

Pushpa Kumari’s influences are purely India. Her voice is authentic and her vision non-compromised. She is stimulated by the complexity of modern India and those interests direct her work. Her approach to drawing may be personal and intuitive, or direct and confrontational, yet always distinctly Indian.

Despite the fact that Kumari’s art can be a challenge to interpret for viewers who are unfamiliar with the more nuanced aspects of Indian culture, Kumari has been invited to exhibit internationally. In 2016 her work was included in the prestigious Eighth Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art at Queensland Art Galley / Gallery of Modern Art. She has also participated in several museum exhibitions in the United Kingdom, including “Telling Tales”, a 2013 show at the National Museums Liverpool.

For many years there have been undertakings by individuals and organizations to “help” the artists of Madhubani. Some of these efforts have been simply focused on marketing assistance, yet other involvements were more invasive. New subject matter has been suggested or encouraged to Madhubani artists from people outside of their own culture. The outcome of this teamwork has been mixed; some efforts have resulted in expanding the possibilities Madhubani art but have also generating work that is simply decorative and lacking honest substance.

It is essential to note that the remarkable innovations seen in Kumari’s art have nothing whatsoever to do with outside influencers. She is a woman who has been on a deep and profound artistic journey since she was a child. Her drawings express the urgency of a visionary determined to express ideas on the page, but always on her own terms. Upending convention, Kumari is driven to show that an artist informed by heritage can and should have a voice in contemporary society. She is keenly aware of what she has to offer as an observer of the world she inhabits.