Drawing Form - Sculpture Magazine, January / February 2017

Jill Bonovitz is an artist with an intensely personal aesthetic sensibility. Using the simplest of materials, she builds wire sculptures with an orientation that is quiet, intimate, nuanced, and poetic.

Generally known for her work with clay, Bonovitz creates idiosyncratic ceramic shapes with a restrained use of hue. The matte opacity of her glaze gives each object a visual weight. Although small in scale, these forms appear substantial.

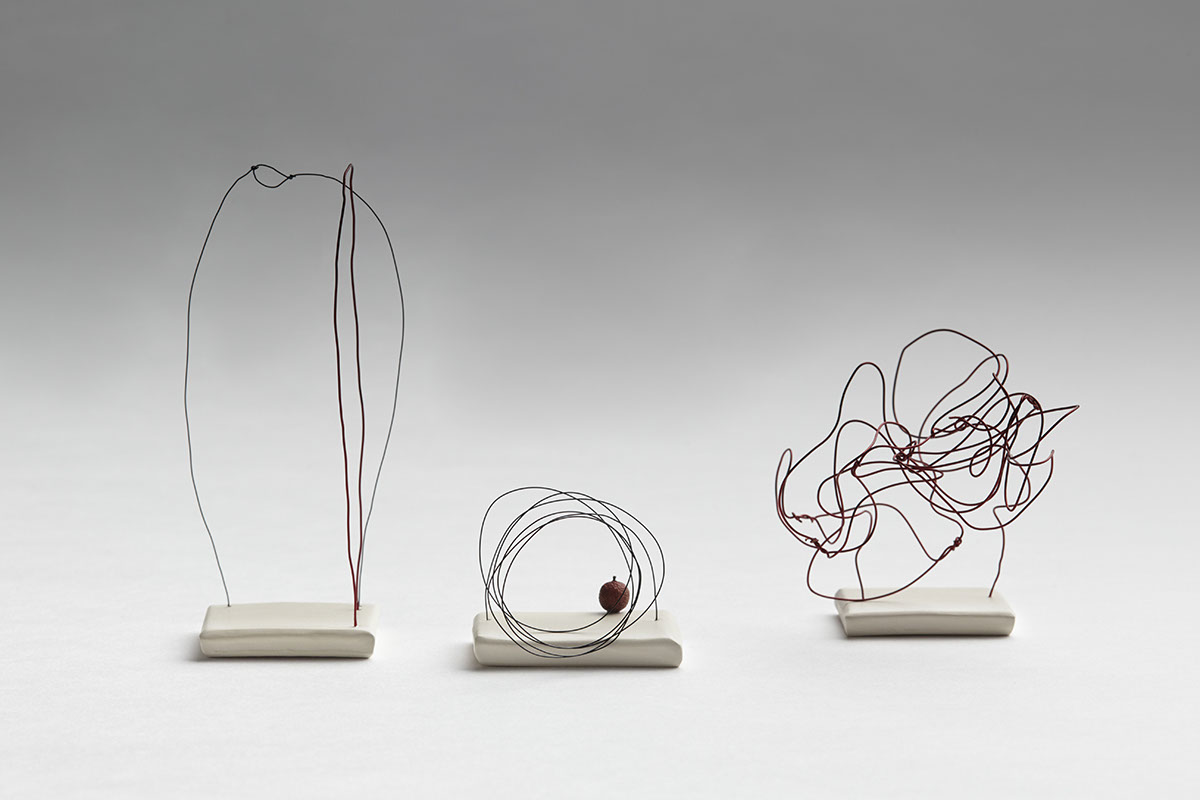

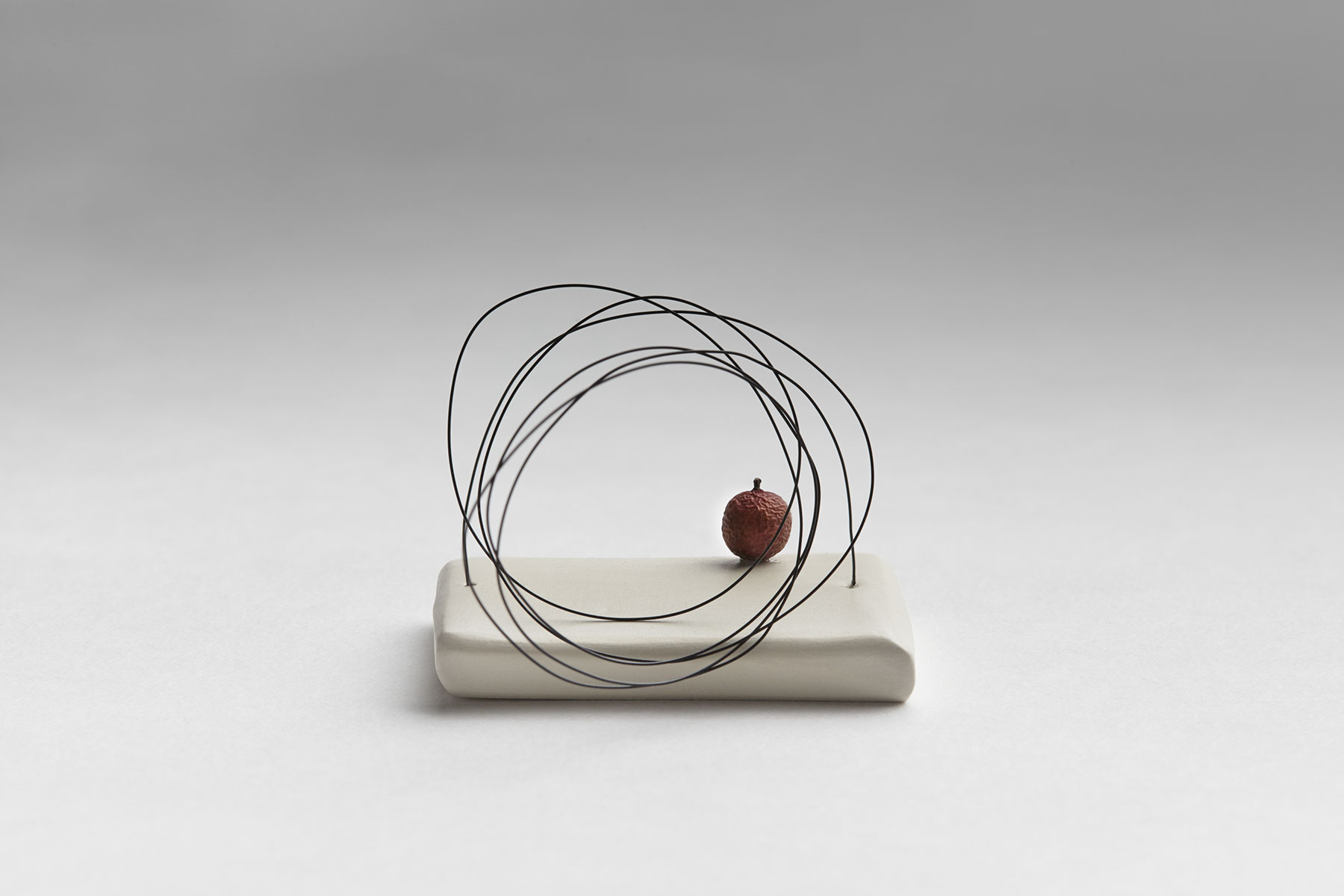

In addition to her clay pieces, for the past fifteen years Bonovitz has been using thin metal wire to make sculpture. Bending and twisting elements, she creates line drawings which have been given form. In contrast to her ceramics, these works appear to elude gravity. Lines suggest movement; wires intersect at points, catching light randomly.

These lyrical and rhythmic wire sculptures appear structurally precarious. They are fabricated in a manner that seems more haphazard than skilled. Yet Bonovitz is an exceptionally informed artist who always creates work with the most focused intent. With her wire pieces she offers forms both delicate and subtle. It is this world, the domain of the fragile, the vulnerable, and the exposed that Bonovitz occupies.

Wire elements came into Bonovitz’s art in a curious and roundabout way. It was not the result of a deliberate pursuit or artistic exploration. Rather, noticing that fruit was rotting over time in a bowl in her kitchen, she crafted a wire basket thinking this container might stop the decay. The basket was made of a much thicker wire than the sculptures that were to come later. This solution was unsuccessful as the fruit still deteriorated, so she abandoned this idea.

However there was something about this basket that resonated with Bonovitz. At the time, she was not clear why this object was of interest. So she chose not to discard it, and instead, without any specific thought, secured the basket to a wall in her studio. Over time, the object suggested possibilities and Bonovitz began to experiment with wire.

The first works that followed resembled baskets made to be placed on a pedestal or shelf. They are constructions that suggest the possibility of containment. It is tempting to see these pieces as objects that could hold other things. But, in fact, the connection to function is conceptual. These sculptures imply shapes without actually defining one.

Later, pieces were built to hang on the wall or suspend from the ceiling. In these efforts the impression of drawing in space is the most apparent. It is as if the artist has found a magic pen that can render in three dimensions. These works convey an energy seen in drawings made with speed and spontaneity. Although in the strictest sense, it may be accurate to refer to these works as sculptures, they are more aligned with installation, offering an experience rather than presenting a defined object. Bonovitz’s wire pieces, whether on a wall or suspended, are about the moment and less about permanence or structure.

Recently, Bonovitz has been making diminutive sculptures that are her simplest to date. Working with a small base, she attaches one or two wires, and then making only a few manipulations, completes the piece. These objects seem like models for much larger constructions, but in fact are hyper-intimate finished sculptures. This work reveals Bonovitz at her purest; creating art with only what is absolutely essential.

This sensibility, the notion of things reduced and attentively nuanced in detail, comes from the artist’s long time attraction to a particular aspect of Japanese art. In Japan, the concept of Mingei, a sense of beauty that can be found in the common place, was first expressed in the early 20th century. Although originally applied to folk craft, this aesthetic orientation has infiltrated the world of painting and sculpture. Mingei is the conceptual underpinning that grounds Bonovitz’s art.

For thirty years Bonovitz has occupied the same studio, a third floor loft in South Philadelphia. This space functions as a sanctuary, a place to work, but also an environment where all things reinforce a frame of reference. Collected objects coexist with sculptures both realized and in process. New works as well as older pieces can be seen in a range of mediums. There is a limited color palette that is consistent throughout the loft. The entire studio defines this artist’s personal narrative.

Like many creative individuals who find respite in their studios, this loft is a place for Bonovitz to concentrate without distractions. It is a setting with a consistent sensibility, a large room with a distinct beauty. Bonovitz needs such a space more than most. Her involvement in the art world is complex. In addition to exhibiting sculpture in museums and galleries, she serves on the boards of several arts organizations.

With her husband, she has assembled one of the most significant private collections of American outsider painting and sculpture, which has been exhibited at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Their collection is a promised gift to the museum. Bonovitz has also contributed an important group of embroidered textiles from India to the same institution. These donations have been the subject of two definitive catalogs.

As a museum board member, adviser and collector, Bonovitz is tasked to consider many types of art. Most are fundamentally different from her own. To stay grounded, focused, and true to her vision, time in the studio is critical for her.

In a sense, this studio is an installation work in itself. It is a space filled with details in a range of materials. Pieces built by Bonovitz are arranged next to art she has carefully collected. Each object appears responsive to the next. Things are added and taken away, the impression of work in progress and exploration resonates from all surfaces.

It is from this studio that Jill Bonovitz, without pretense, reveals the compelling that can be found in the ordinary. Thoughtfully, she creates humble sculptures that rest on pedestals, attach to walls, and hang from ceilings. She speaks softly through the work, offering an experience, but never demanding an encounter.